Life magazine, published a

fascinating book with writer

Naomi Wax, called: What We

Keep. The book is based on

150 interviews with people

who shared “the one object

that brings them joy, magic

and meaning.” Each one of

the people interviewed, from

all walks of life: celebrated

authors, business leaders,

astronauts, nuns, autoworkers,

etc., talks about the

emotional significance of the

single selected object. Objects

selected include pieces of

furniture, old musical instruments,

items of clothing,

dishes and cooking appliances,

toys, a rusty trowel, a first

computer, an ancient transistor

radio, an old projector,

and even a 1927 motorcycle

and a Chevy truck from 1948.

The stories of 150 personal

treasures prompt readers to

review their own collection

of cherished objects, try to

understand not only what

they value but also why.

Some experts believe that one should be

wary of nostalgia as it lures one with memories

of “the good old days.” But this is not necessarily

bad. Memories of good days should be

cherished, and even mementos associated with

loss add meaning. The objects we choose to

keep tell our story. They speak volumes about

what is important to us, provide a sense of continuity,

and may offer comfort during difficult

times. Speaking personally, the things I keep

help me celebrate memorable times: chapters

of my narrative that ended, people who are

no longer here, places I spent time in, special

events. I do know that memories are encoded

in our brain and kept in our hearts, but physical

items representing those memories are tangible

reminders. They also remind us of how fast

time flies, how important it is to be grateful

for what is, to cherish every day...

I also love showing some of these items to

my grandchildren and telling them the related

stories. Actually, my grandson, currently a

senior at Princeton University, wrote a term

paper on the ways history is preserved in our

family, where – perhaps due to the impact of

the Holocaust – history is pivotal. I will never

forget the day my father went to a box in his

closet and shared with me the letters his father

(who died in Auschwitz exactly a week before I

was born) had sent him from occupied Poland.

I felt like I was meeting a grandfather whom I

never got to meet in person, a connection to my

roots. My parents had very few mementos from

their past. They left burning Europe as young

people just before WWII, with one suitcase

each. They held on to the few mementos they

brought along for dear life. In a recent visit

to my daughter’s new home, I took pleasure

in seeing some of these items on her shelves.

In a presentation on Living With and Beyond

Loss, relevant to the era of the current pandemic,

I spoke about “linking objects” – a term

coined by psychiatrist Vamik Volkan years ago.

“Linking objects” are visual reminders connecting

us to loved ones who are no longer here or

are far away and sorely missed. These actual

objects become symbolic representations that

help us viscerally feel the connection: letters,

pictures, gifts, items loved ones used. Like my

mother’s jacket, a gift from me to keep her

warm on our walks, which I now wear when I

need to feel her presence. Or my Daily Planners

from years past which help ignite memories

of special times. Or signs from a “secret club”

I created way back when with my now-adult

grandchildren under our-then home: We called

it “The BEAN Club” – BEAN being an acronym

for Ben, Ella, Alec, Nurit. When their younger

cousin Sam was born, we changed the club’s

name to “The BEANS Club”, the S representing

Sam’s name...

Oscar Wild said, “Memory is a diary we

all carry about with us.” If memory is a

diary, keepsakes are exhibits, small personal

museums of the history that makes up each

of our stories. During the pandemic, I pulled

out memory boxes, planning to go through

mementos piece-by-piece, in order to decide

whether all still deserve to be kept. I recalled

Dr. Seuss’ observation: “Sometimes you will

never know the value of a moment until it

becomes a memory.” Honoring the value of

special moments, even retroactively, is one way

to infuse our narrative with meaning.

____________________

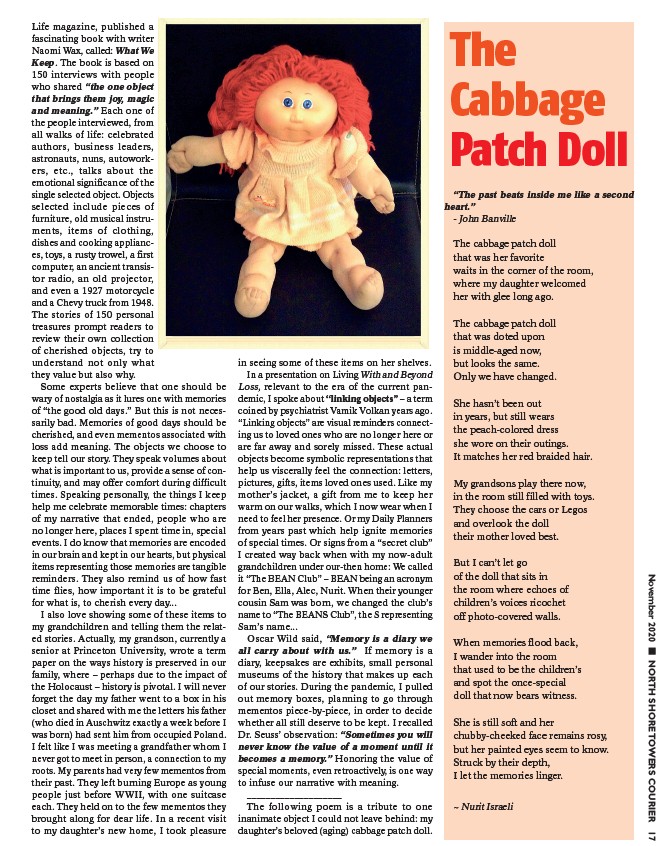

The following poem is a tribute to one

inanimate object I could not leave behind: my

daughter’s beloved (aging) cabbage patch doll.

The

Cabbage

Patch Doll

“The past beats inside me like a second

heart.”

- John Banville

The cabbage patch doll

that was her favorite

waits in the corner of the room,

where my daughter welcomed

her with glee long ago.

The cabbage patch doll

that was doted upon

is middle-aged now,

but looks the same.

Only we have changed.

She hasn’t been out

in years, but still wears

the peach-colored dress

she wore on their outings.

It matches her red braided hair.

My grandsons play there now,

in the room still filled with toys.

They choose the cars or Legos

and overlook the doll

their mother loved best.

But I can’t let go

of the doll that sits in

the room where echoes of

children’s voices ricochet

off photo-covered walls.

When memories flood back,

I wander into the room

that used to be the children’s

and spot the once-special

doll that now bears witness.

She is still soft and her

chubby-cheeked face remains rosy,

but her painted eyes seem to know.

Struck by their depth,

I let the memories linger.

~ Nurit Israeli

November 2020 ¢ NORTH SHORE TOWERS COURIER 17