“Wind” Talker

Speaker John Kenrick returns with enlightening look

at “Gone with the Wind”

STORY AND PHOTOS

BY STEPHEN VRATTOS

“Frankly, Pansy, I don’t give a

damn!”

It’s difficult to imagine this

iconic film quote, never mind the

character to which it is directed,

having quite the same impact, if

any import at all, had the Margaret

Mitchell classic, “Gone with the

Wind,” been published as the

author originally intended. But

that’s exactly what might have

happened had not the book’s

publisher, Macmillan, not wisely

suggested the literary heroine

be rechristened “Scarlett,” from

Mitchell’s intended “Pansy.”

Toothsome trivia, such as this,

is what makes attending a John

Kenrick lecture so fun and surprising.

Courtesy of the University

Club, the entertainment teacher/

historian returned to North Shore

Towers Thursday evening, March

29, to address a standing-room-only

audience in the large card room

to pontificate on the silver screen

adaptation of the Margaret Mitchell

classic. Combining vintage movie

clips and images with music and

mouthwatering memorabilia, deftly

delivered with masterful showmanship

and unforgiving personal

commentary, Kenrick’s are always

must-see events.

The film, which will celebrate 80

years in 2019, can trace its origins

to a fortuitous accident suffered

by Mitchell in 1926. At the time a

reporter for the Atlanta Journal,

the would-be author began the

novel, pecking away at a typewriter

her husband had bought her as

a means of whiling the way the

weeks of convalescence she faced

from a badly sprained ankle. The

ankle’s healing was completed far

more quickly than the 1,073-page

book, which Mitchell eventually

took nine years to finish. Published

in 1936, “Gone with the Wind”

was an instantaneous bestseller.

Mitchell tentatively titled her

tome, “Tomorrow Is Another Day,”

from its last line; a moniker which

seems trite in hindsight and certainly

lacking the musicality and

alliterative appeal of the resultant

name. For that, she turned to the

1894 poem “Non Sum Qualis

Eram Bonae sub Regno Cynarae”

by English poet/novelist Earnest

Dowson, the third stanza of which

begins…

“I have forgot much, Cynara!

gone with the wind,

Flung roses, roses riotously with

the throng,

Dancing, to put thy pale, lost

lilies out of mind…

The book’s page-to-screen story

is as epochal as “Gone with the

Wind” itself. The war to secure

its rights alone reads like a lurid

romance. A staff reader at MGM

urged Louis B. Mayer to obtain

them, but the cinematic head was

dissuaded by Irving Thalberg,

MGM producer of such august

adaptations as “Grand Hotel

(1932),” “Mutiny on the Bounty

(1935)” and “Romeo and Juliet

(1936).” At the time, Thalberg’s

work had already brought the

studio three Best Picture Oscars;

his advice as weighty as the movies

he produced. “No Civil War

movie ever made money,” he told

Mayer, both men seeming to forget

D. W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation

(1915).” Or perhaps not, instead

both refusing to acknowledge the

scurrilous celluloid love letter to

the Ku Klux Klan, success or no.

While Mayer dawdled, independent

producer David O. Selznick

swept in, grabbing the rights for a

then unprecedented $50,000, with

the help of good friend and millionaire

John Whitney, who put up

half the money for the book’s movie

option, after being persuaded to

do so by Talent Agent Kay Brown.

As large a sum as that was for the

time, the price tag would have been

much steeper had the sale stalled,

for soon thereafter, Mitchell’s

one and only work received the

Pulitzer Prize. Selznick’s drive

to buy, however, may have been

spurred by something other than

business savvy. He was betrothed

to Mayer’s daughter, Irene, but

had no love for his Father-in-Law

who he believed cheated his own

dad, once vowing “I will get my

revenge!”

As fate would have it, Selznick

would have to work with his wife’s

father, after all. As an indie producer,

he had no long-term contract

players on his payroll and subsequently

needed to “borrow” from

Mayer, Clark Gable to portray

Rhett Butler, when first choice

Gary Cooper turned down the role.

“‘Gone with the Wind’ is going to

be the biggest flop in Hollywood

history,” Cooper notoriously later

remarked after refusing the job.

“I’m glad it’ll be Clark Gable who’s

falling flat on his nose, not me.”

Clark was equally unwilling

to take the role, fearing he could

never live up to Mitchell’s literary

leading man, a feeling with which

the author agreed. The beloved

actor’s stonewalling eventually

landed him a salary with which he

could agree, one which would help

him pay for the divorce from his

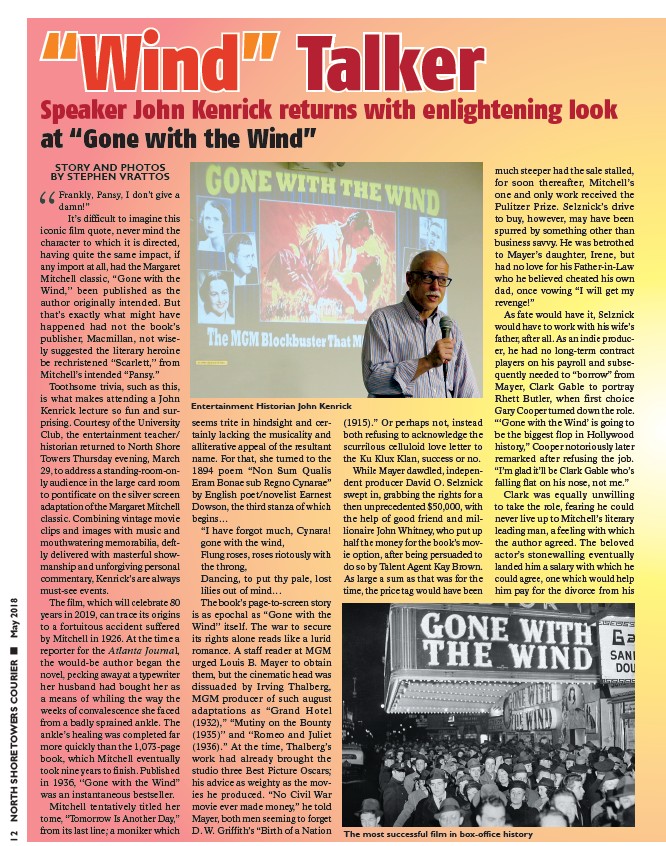

Entertainment Historian John Kenrick

The most successful film in box-office history 12 NORTH SHORE TOWERS COURIER ¢ May 2018