BRONX TIMES REPORTER, O BTR CT. 29-NOV. 4, 2021 9

ARE THE NEW

GROCERY

DELIVERY

APPS WORTH

IT TO NYC

CONSUMERS?

Delivery was swift. Only

9 minutes after placing the

order, the courier arrived,

handed over the goods, and

went on his way.

A four-pack of Scott toilet

paper at the “corner store”

runs for $6.99, a dozen eggs,

cage-free are $4.99, Almond

Breeze is $5.99, a loaf of Arnold

White Bread is $4.69.

Shoppers who want to get

a head start and place an order

during off-hours hoping

to receive their groceries fi rst

thing in the morning are out

of luck. Like regular stores,

the app is “closed” from 11 pm

to 8 am, and orders can’t be

placed during those times.

Not everything was easy

Orders placed with JOKR

and Gorillas were less successful.

Despite both companies

advertising delivery in

Long Island City, neither had

a warehouse close enough to

deliver on the border between

LIC and Astoria.

Still, fi lling a cart on the

apps was similar in price to

fi lling one in-person, though

the same brand discrepancies

exist — if you’re hoping to

fi nd a house-brand jug of milk

or can of vegetables on an app,

you’re likely out of luck.

A small order with Gorillas

— which was just a hypothetical,

since we couldn’t

complete the transaction –

amounted to $18.84 for the

groceries themselves, plus

$1.80 delivery fee, $0.28 in

sales tax, and a $6 tip — $27.33

in total.

The products themselves

were priced similarly to what

we found in a nearby Food

Universe — a grocery store

owned by Key Food — and in

some cases less expensive.

A can of Del Monte Green

Beans on Gorillas was 50 percent

off, $1.00, a four-pack

of Scott toilet paper, $4.99, a

2-liter bottle of Coca-Cola,

$2.69, a pint of Ben & Jerry’s

Ice cream, $5.29, and a dozen

Eggland Large White Eggs,

$2.99. What I couldn’t get on

Gorillas was a gallon of dairy

milk — most of their milks

are lactose or dairy-free. I

chose 12 ounces of Ronnybrook

Farm milk for $1.89,

but the real next-best choice

was a half gallon of Battenkill

Valley skim milk, which runs

$4.49.

At Food Universe, the

same dozen eggs costs $3.99,

though the store was running

a “manager special,” on a different

brand of eggs — 3 cartons

of a dozen for $5. A gallon

of 2 percent milk was $3.59,

Green Giant Green Beans

$1.99, the same pint of Ben

& Jerry’s, $5.59, two liters of

Coke, $2.49, and a four-pack of

Scott toilet paper, $5.29.

At a nearby independent

halal grocery store, a gallon

of milk was $3.49, as advertised

by a sign taped to the

front door, 2 liters of any soda,

$2.49, and single rolls of Scott

toilet paper, $1.49.

We had some more trouble

with brands on JOKR. We

fi lled the cart with a bottle of

Palmolive dish soap, $2.99 —

slightly more expensive than

the Food Universe’s most expensive

bottle, which was

$2.79, but on par with a bottle

of Ajax at the halal store – a

four-pack of Scott, $3.79, and

2 liters of Coke, $2.29. The

cheapest eggs, a dozen Alderfer

“humane certifi ed” large

eggs, was $3.49, the cheapest

loaf of bread, “Mestemacher

Fitness Bread,” $3.99, compared

to a $2.29 loaf of storebrand

Italian bread at Food

Universe.

We couldn’t fi nd canned

green beans, but the closest

item – a 12oz bag of fresh

beans — was $3.99, and a halfgallon

of Organic Valley 2

percent milk was $4.79.

All together, the haul was

$25.51, plus $0.81 in taxes and

a $6.00 tip — $32.32 in total. At

the time, the app noted that

delivery would likely take

longer because of the heavy

rain.

Of course, your experiences

with these apps may

vary.

‘It’s an atrocity’

Some aren’t sold on the

idea of grocery delivery apps,

no matter how convenient or

cost-effective the companies

promise they are.

Friends Jasmine Lee and

Kahlil Robert Irving prefer to

support local businesses and

know the owners.

Lee, who lives and works

in Chinatown, thinks “it’s an

atrocity.” She prefers to pick

her produce and disagrees

that using a grocery delivery

app is faster.

“It’s actually not very convenient,”

Lee said. “What’s

more convenient than just

running down the street to

your bodega?”

Kahlil Robert Irving, who

lived in Brooklyn and now

calls St. Louis, Missouri

home, felt that the constant

evolution of trying to fi gure

out how to make money by offering

more convenience was

quite problematic for human

interaction.

“It’s about being human.

This kind of evolution of capitalism

is dehumanizing,”

Irving expressed. “It’s demonizing

the possibility of

relationships or sustaining

interpersonal relationships.”

David Bishop, a partner

with Brick Meets Click, a consulting

company that works

with “conventional” grocery

stores, said those established

brick-and-mortars know best.

“The retailer’s inventory

ordering system is fairly automated

in the sense that

it’s looking at historical buying

patterns, overlaying that

with other causal factors

like weather, and incorporating

what the current sales

trends are to replenish that

stock,” Bishop said. “A traditional

grocery store has

been around a long time, so

their understanding of what

sells and what doesn’t is far

greater than what a new entrant

who’s coming in and

trying to serve a specifi c need

may be able to do.”

Quick-delivery apps, for

now, are focused in dense urban

areas. Since each small

warehouse serves a small

area — maxing out at 2.5

miles, in the case of 1520 —

there need to be a lot of people

living there.

The cost of purchasing

enough land or renting out a

large enough building to run

a traditional grocery store

is much higher in New York

City and the tri-state area

than in rural areas, Bishop

said, so operating out of a

store with a smaller footprint,

and that doesn’t invite shoppers

in, means those companies

have “comparable costs,

although lower to traditional

brick-and-mortar grocers.”

All stores try to reduce

waste, he said, because, in the

end, it eats into their profi ts

— but he said the proof that

carrying fewer items would

result in less waste “remains

to be seen.”

The third installment of

“The Race to Deliver,” scheduled

to run on Nov. 5, will focus

on the potential and current

impacts grocery delivery

apps may have on bodegas,

grocery stores and other brickand

mortar businesses.

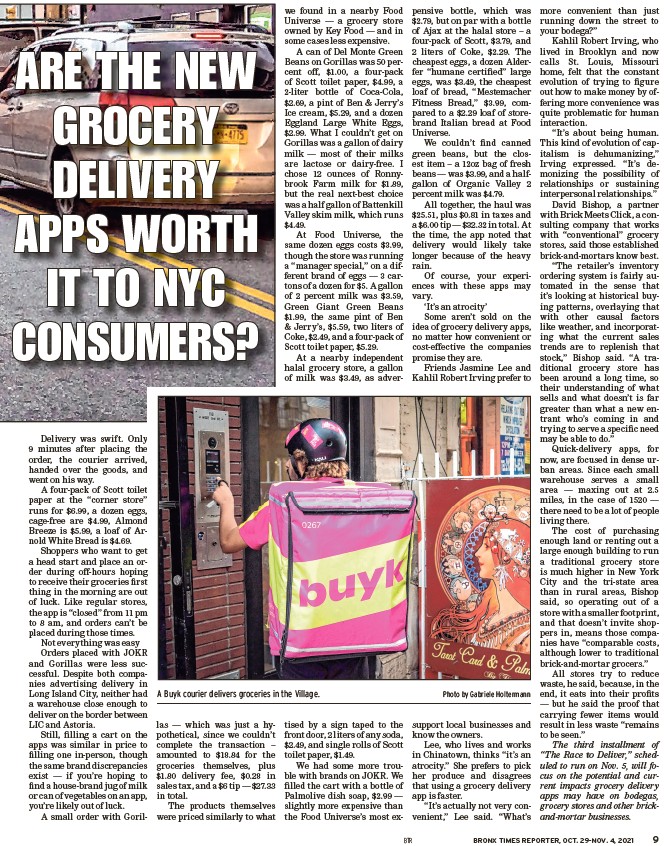

A Buyk courier delivers groceries in the Village. Photo by Gabriele Holtermann