Medallion Matters

by CATE CORCORAN

Popular in nineteenth century homes, plaster ceiling medallions

offer a visual transition and seat for a light fixture

in important rooms. Their elaborate bas-relief designs also

helped hide soot from oil and gas lamps.

They were de rigueur in the main entrance hall, parlors,

dining room, and large bedrooms. In Brooklyn, you will

not find them in small side bedrooms, halls, or bathrooms,

where wall sconces would be used, nor in kitchens, where

a J-hook might hang over the sink.

As one might expect, styles of medallions changed along

with other interior fashions and are one of several clues to

the age of a building. Greek Revival and Italianate medallions

often employ leaf motifs. At their most simple, such

a medallion might consist of leaves attached directly to

the ceiling and radiating out from a rosette in the center.

Plain-run moldings or beads might encircle the fanciful

center decoration. Elaborate variations in homes of the

well to do might be layered over bits of trellis or other

background patterns and studded with blossoms. A medallion

could be made entirely by hand on site, cast off site

in a mold, or built up using a combination of methods.

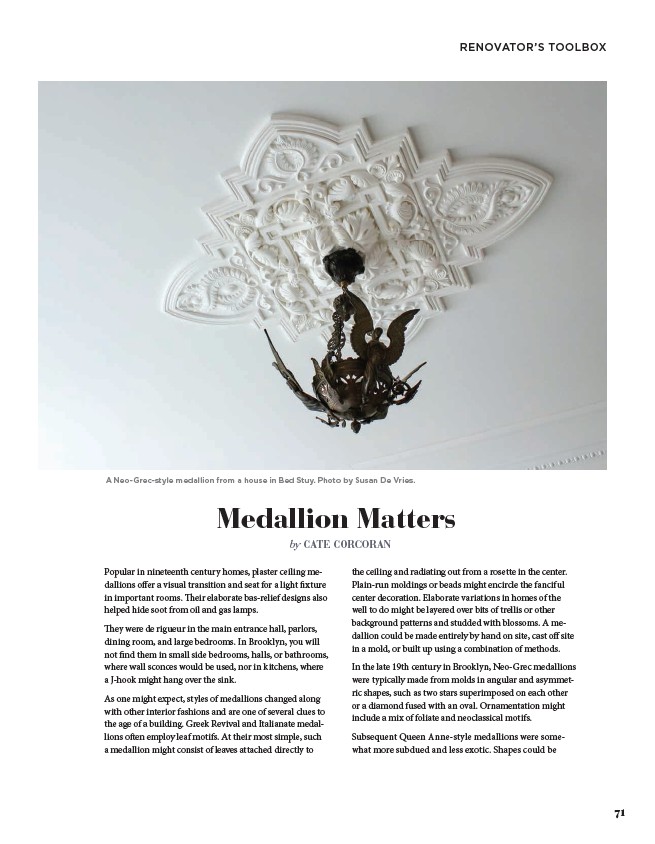

In the late 19th century in Brooklyn, Neo-Grec medallions

were typically made from molds in angular and asymmetric

shapes, such as two stars superimposed on each other

or a diamond fused with an oval. Ornamentation might

include a mix of foliate and neoclassical motifs.

Subsequent Queen Anne-style medallions were somewhat

more subdued and less exotic. Shapes could be

71

RENOVATOR’S TOOLBOX

A Neo-Grec-style medallion from a house in Bed Stuy. Photo by Susan De Vries.