84 LONGISLANDPRESS.COM • MARCH 2018 84 LONGISLANDPRESS.COM • SEPTEMBER 2017 84 LONGISLANDPRESS.CO M • SEPTEMBER 201-----------TUTU111

REAR VIEW

Still, she persisted

How L.I.’s Irene Corwin Davison helped win women’s right to vote

By ANNIE WILKINSON

In mid-1800s America, citizens

were defined as male, not female;

nonwhite men and freed slaves

could vote, but women couldn’t;

and married women could not own

property in their own right or make

legal contracts on their own behalf.

To protect her rights, Irene Corwin

Davison never married, instead

working to improve unfair working

conditions for women and children,

inadequate public health programs,

and discriminatory education

practices.

Tall and intelligent, Davison was

a dedicated reformer, organizer,

marcher, poll-watcher, canvasser,

and generous member of the

community. She instigated change

using her plucky personality, her

financial freedom — and a sturdy

old wagon.

WHO WILL DARN OUR

SOCKS?

Her father, Oliver Davison, an area

pioneer, ran the grist- and saw mill

he inherited. One of the few free

entry ports, the “Near Rockaway”

business prospered.

His daughter, Irene, was born in

1871. After completing college

preparatory courses at Brooklyn’s

Packer Collegiate Institute and

graduating from Pratt Institute, she

taught art in Jericho schools, and

was one of the first women to open

her own insurance agency.

Years earlier, New York State

had been dubbed the “Cradle of

the Women’s Movement” after

the organized women’s rights

convention in Seneca Falls in 1848.

At the convention’s heart was the

quest for suffrage: the right to

vote in political elections. Their

Declaration of Sentiments outlined

rights that women citizens should

have, by adding to the Declaration

of Independence “all men and

women are created equal.”

The opposition reacted: One

newspaper even ran editorials

asking who would darn socks if

women got the vote.

During the Civil War, suffragists

concentrated on abolishing slavery.

By the late 1890s, they regrouped,

joining the Progressives. With

social services struggling with

industrialization, urbanization, and

European immigration, suffragists

fought to open health clinics,

outlaw child labor, and improve

factory conditions.

A BIGGER CROWD

In 1902, in her early 30s,

Davison joined women from East

Rockaway’s oldest families to

exchange books. Drawing strength

from reading, by 1906, they had

built the new East Rockaway Free

Library. Davison and her two older

sisters worked for suffrage, which

was making headway.

In March 1913, the day before

U.S. President-elect Woodrow

Wilson’s inauguration, crowds were

expected. But the Pennsylvania

Avenue suffragists upstaged him.

“Where are the people?,” he reportedly

asked, and was told, “On the Avenue

watching the suffragists parade.”

Those 8,000 marchers called for a

constitutional convention. Many

were attacked by the mostly male

spectators; police allegedly ignored

the violence and 100 marchers

were hospitalized. The event

generated national attention and

congressional hearings — but no

legislation.

STILL, SHE PERSISTED

Several months later, Davison

helped engineer a hugely successful

publicity stunt. It was July 1,

summer’s peak, when she left

Manhattan, drawn by their horse

“Suffragette” in a one-horse shay

built in 1776. The wagon bore

banners saying, “Votes for Women”

and yellow knapsacks (the color of

suffrage). Davison, then 42, rode

with suffragist Edna Buckman

Kearns, dressed in hot minutemen

garb, and Kearns’ daughter, 8-yearold

Serena.

They headed to Long Island for a

month of speeches at meetings and

rallies. Another “wagon woman,”

Rosalie Jones of Cold Spring

Harbor, often drove her yellow

wagon next to them. They were

among many activists crisscrossing

the Island and major U.S. cities

from 1913 to 1915.

The news-savvy Davison helped

stage a September 1913 event that

drew hundreds of women and men.

For the Aerial Party encampment

on the Hempstead Plains aviation

field (now Roosevelt Field), 50

women slept in a hangar. Davison

later worked as a poll watcher,

asking Sayville voters to sign

statements saying that the vote

should be granted to New York

women in 1915. The following

year, Davison became president of

the South Side Political Equality

League of Lynbrook and East

Rockaway. When her father died in

1916, the 45-year-old, considered

an “old maid,” sold his farm to

create one of the Island’s first

housing developments.

DETERMINED AND

DISTINGUISHED

In 1920, after decades of activism,

women were granted the vote in

national elections. The New York

Times wrote that women succeeded

“despite the fears of anti-suffragists

that when a woman received the

right to vote, ‘political gossip would

cause her to neglect the home,

forget to mend our clothes and

burn the biscuits.’”

Davison continued educating

women on the importance of

voting. The League of Women

Voters named her Nassau County

outstanding suffragette and listed

her name on a bronze plaque in

Albany. She died on November 12,

1948, and was buried in Rockville

Cemetery in Lynbrook.

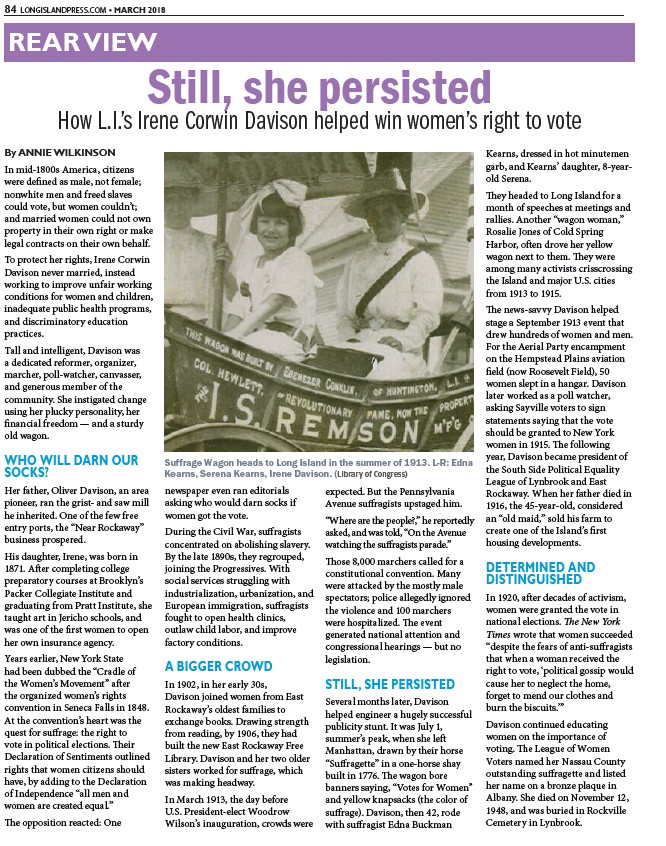

Suffrage Wagon heads to Long Island in the summer of 1913. L-R: Edna

Kearns, Serena Kearns, Irene Davison. (Library of Congress)