THE RACE TO DELIVER: How grocery delivery app wo

By Kirstyn Brendlen and Gabriele

Holtermann

This is the fifth and final installment

in amNewYork Metro’s five-part series

examining the proliferation of grocery

delivery services across the city, and

how they treat their fleet of delivery

workers.

Last year, as the pandemic swept

New York City for the first time and

forced businesses to close temporarily

or altogether, there was one industry

that seemed to be perfectly suited to

survive: food delivery.

Demand for grocery delivery through

apps like Instacart soared, and Bronxbased

giant Fresh Direct launched an

express delivery option, where customers

could choose from a limited

number of products available in just a

few hours.

New Yorkers were also ordering more

meals through apps like Uber Eats and

DoorDash to get meals from restaurants,

which were largely pick-up and

delivery only.

New quick-commerce grocery delivery

apps are at the nexus of those two

markets. Companies like JOKR, Gorillas,

and Fridge No More have expanded

rapidly in the last year as they filled the

demand for groceries delivered within

fifteen minutes of placing the order via

app, with low or nonexistent delivery

Caribbean L 26 ife, NOV. 26-DEC. 2, 2021

fees and no order minimums.

At the center of all of those businesses,

over the user experience of placing

an order on an app or the variety of

items available, are the delivery workers.

Couriers zipping by on electric

bicycles with an insulated bag strapped

to their back have become ubiquitous

in the city in the last decade, and now

passers-by might be seeing a host of

new uniforms and branded e-bikes as

quick-commerce apps continue their

steady march forward.

Employees, not contractors

Those uniforms and e-bikes mark a

stark contrast between apps like JOKR

and Gorillas and UberEats. The majority

of delivery workers who deliver for

UberEats and DoorDash are contracted

or “gig” workers — essentially freelancers.

They pick up work when it’s

available, but aren’t employed by the

company formally — there’s no guarantee

of hours, wages, tips, no time off

or benefits.

At most of the new grocery delivery

apps, couriers are full or part-time

employees, with set schedules and, in

some cases, benefits.

“Unlike many delivery and on-demand

service companies, all our workers

are full-time and part-time W2

workers who are provided minimum

wage on an hourly basis,” a Gorillas

spokesperson said. “On top of that,

they receive 100% of their digital tips

at the end of each month, and customers

are made aware of this at every

transaction. In addition to compensation,

they’re entitled to workplace benefits,

paid breaks in compliance with

local regulations, and the opportunity

to return to the warehouse to refresh

after each delivery.”

Gorillas riders are also provided with

a company e-bike and gear including

helmets, riding gloves, and a vest,

according to their website.

Couriers for JOKR are also employees

with benefits, co-founder Tyler Trerotola

told Brooklyn Paper, and the

company has made an effort to be

“employee first.”

“We’ve made a conscious decision

that we want these employees to have

benefits, we want them to feel part of

the company,” he said. “The nature of

this business is very much a consumerfocused

business, it’s very much about

experience. Having happy employees —

and employing them is furthering that

customer experience. And then also,

obviously, be better for that employee.”

Dangers on the job

Demand for fair working conditions

and more protections under the law

exploded last year, driven mostly by

Los Deliveristas Unidos, a collective

of mostly-immigrant delivery workers

who banded together as they worked

long, difficult hours through the pandemic

without the protection or hazard

pay offered to so many essential

workers.

Even outside of working long hours

in the cold, without the guarantee of an

hourly minimum wage or tips, the job

is dangerous. Many workers are hit and

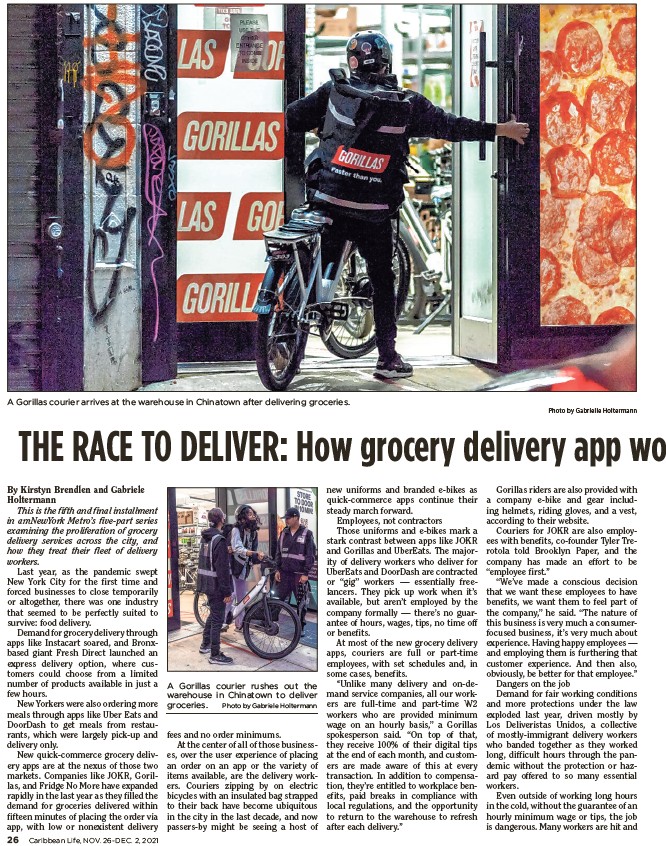

A Gorillas courier arrives at the warehouse in Chinatown after delivering groceries.

Photo by Gabrielle Holtermann

A Gorillas courier rushes out the

warehouse in Chinatown to deliver

groceries. Photo by Gabriele Holtermann