44 LONGISLANDPRESS.COM • OCTOBER 2017 44 LONGISLANDPRESS.COM • SEPTEMBER 2017 44 LONGISLANDPRESS.CO M • SEPTEMBER 201-----------TUTU111

FOOD & DRINK

Wheels of fortune

For Bridgehampton’s Ludlow family, cheese is a whey of life

By ERIC VOORHIS

Peter Ludlow reached into a small, straw-lined

enclosure and leaned toward a three-week-old

Jersey cow wearing a yellow nametag. It said

“Kreme.” The young calf sniffed Ludlow’s hand,

looking up with large brown eyes, and then

retreated with an awkward stumble.

“They’ll get super tame with plenty of hand

treatment,” said Ludlow. “You can see how

curious they are – a lot of personality. They all

get names.”

Kreme is part of the growing herd at Mecox

Bay Dairy, an artisan cheesemaking operation

in Bridgehampton that produces six styles of

cheese that are sold at farm markets throughout

the summer and to East End restaurants and

cheese shops. Pete’s father, Art Ludlow, launched

the business in 2003 after deciding it might be

more profitable than his other venture at the

time: potato farming. Now, Art’s two sons, Pete

and John – 30 and 28 – have started working for

the business full-time with hopes of scaling up

the operation.

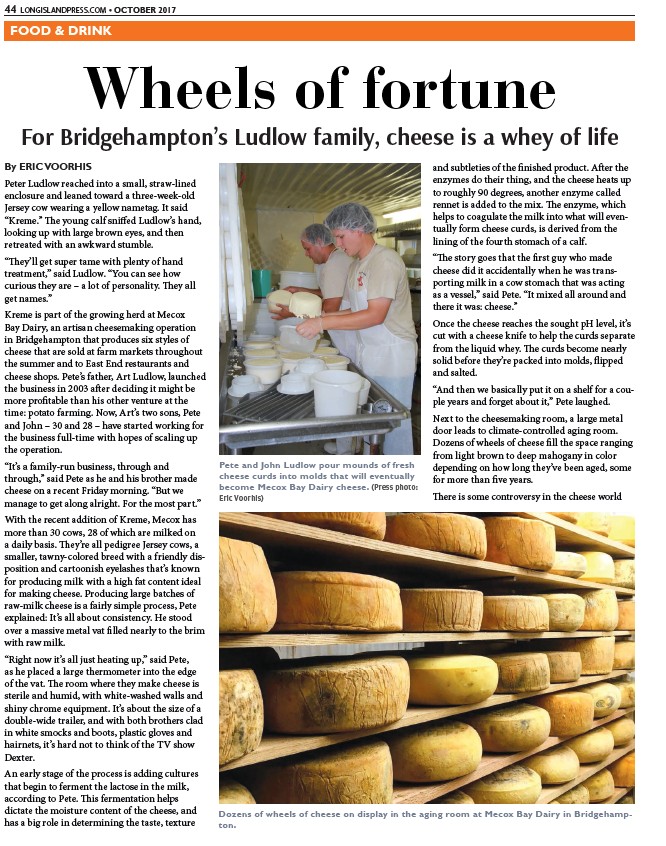

“It’s a family-run business, through and

through,” said Pete as he and his brother made

cheese on a recent Friday morning. “But we

manage to get along alright. For the most part.”

With the recent addition of Kreme, Mecox has

more than 30 cows, 28 of which are milked on

a daily basis. They’re all pedigree Jersey cows, a

smaller, tawny-colored breed with a friendly disposition

and cartoonish eyelashes that’s known

for producing milk with a high fat content ideal

for making cheese. Producing large batches of

raw-milk cheese is a fairly simple process, Pete

explained: It’s all about consistency. He stood

over a massive metal vat filled nearly to the brim

with raw milk.

“Right now it’s all just heating up,” said Pete,

as he placed a large thermometer into the edge

of the vat. The room where they make cheese is

sterile and humid, with white-washed walls and

shiny chrome equipment. It’s about the size of a

double-wide trailer, and with both brothers clad

in white smocks and boots, plastic gloves and

hairnets, it’s hard not to think of the TV show

Dexter.

An early stage of the process is adding cultures

that begin to ferment the lactose in the milk,

according to Pete. This fermentation helps

dictate the moisture content of the cheese, and

has a big role in determining the taste, texture

and subtleties of the finished product. After the

enzymes do their thing, and the cheese heats up

to roughly 90 degrees, another enzyme called

rennet is added to the mix. The enzyme, which

helps to coagulate the milk into what will eventually

form cheese curds, is derived from the

lining of the fourth stomach of a calf.

“The story goes that the first guy who made

cheese did it accidentally when he was transporting

milk in a cow stomach that was acting

as a vessel,” said Pete. “It mixed all around and

there it was: cheese.”

Once the cheese reaches the sought pH level, it’s

cut with a cheese knife to help the curds separate

from the liquid whey. The curds become nearly

solid before they’re packed into molds, flipped

and salted.

“And then we basically put it on a shelf for a couple

years and forget about it,” Pete laughed.

Next to the cheesemaking room, a large metal

door leads to climate-controlled aging room.

Dozens of wheels of cheese fill the space ranging

from light brown to deep mahogany in color

depending on how long they’ve been aged, some

for more than five years.

There is some controversy in the cheese world

Pete and John Ludlow pour mounds of fresh

cheese curds into molds that will eventually

become Mecox Bay Dairy cheese. (Press photo:

Eric Voorhis)

Dozens of wheels of cheese on display in the aging room at Mecox Bay Dairy in Bridgehampton.