60

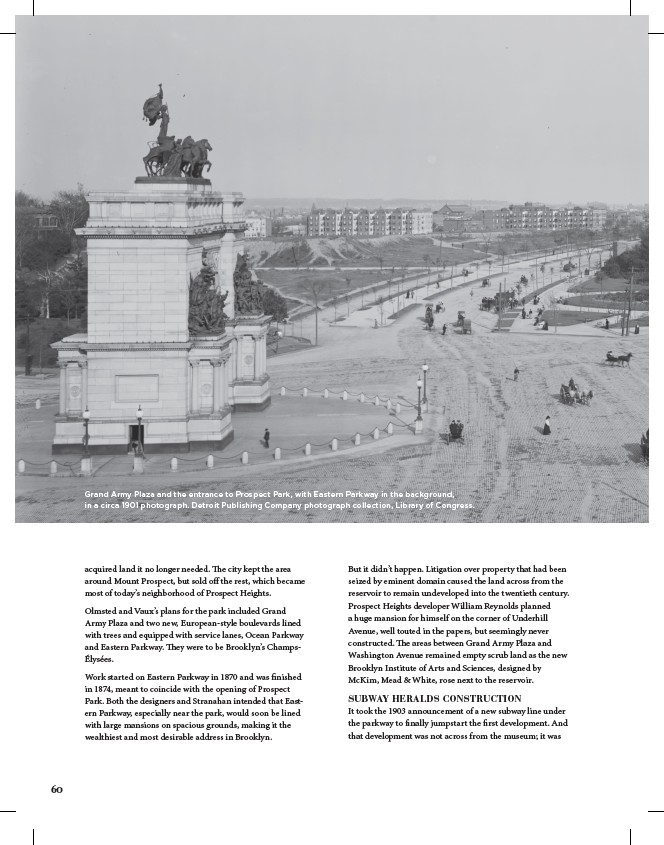

Grand Army Plaza and the entrance to Prospect Park, with Eastern Parkway in the background,

in a circa 1901 photograph. Detroit Publishing Company photograph collection, Library of Congress.

acquired land it no longer needed. The city kept the area

around Mount Prospect, but sold off the rest, which became

most of today’s neighborhood of Prospect Heights.

Olmsted and Vaux’s plans for the park included Grand

Army Plaza and two new, European-style boulevards lined

with trees and equipped with service lanes, Ocean Parkway

and Eastern Parkway. They were to be Brooklyn’s ChampsÉlysées.

Work started on Eastern Parkway in 1870 and was finished

in 1874, meant to coincide with the opening of Prospect

Park. Both the designers and Stranahan intended that Eastern

Parkway, especially near the park, would soon be lined

with large mansions on spacious grounds, making it the

wealthiest and most desirable address in Brooklyn.

But it didn’t happen. Litigation over property that had been

seized by eminent domain caused the land across from the

reservoir to remain undeveloped into the twentieth century.

Prospect Heights developer William Reynolds planned

a huge mansion for himself on the corner of Underhill

Avenue, well touted in the papers, but seemingly never

constructed. The areas between Grand Army Plaza and

Washington Avenue remained empty scrub land as the new

Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, designed by

McKim, Mead & White, rose next to the reservoir.

SUBWAY HERALDS CONSTRUCTION

It took the 1903 announcement of a new subway line under

the parkway to finally jumpstart the first development. And

that development was not across from the museum; it was