41

COURIER LIFE, APRIL 22-28, 2022

Keeping the arts alive in schools

Brooklyn teens take to Carnegie Hall, as arts education struggles to keep its footing

BY MIKAELA WEGNER

A pair of Brooklyn high

school sophomores did their

school proud back in February,

when they took to the stage at

the revered Carnegie Hall to perform

their own, original work.

But the girls and their music

teacher worry that the arts education

that propelled them to one

of the world’s most famous stages

is becoming less and less accessible

to their peers.

Ainka-Amara Gillespie and

Imaani Russell, both 16-yearold

students at Uncommon Collegiate

Charter High School in

Bedford-Stuyvesant, performed

“AfroCosmicMelatopia,” part

of Carnegie Hall’s Afrofuturism

festival, which explores the

intersection of Black culture,

technology, and visions of the

future. Last fall, Gillespie’s music

teacher Briony Price asked if

she’d be interested in collaborating

on a piece for the festival.

In 2019, Price was adjusting to

a high school teacher role in the

US, having grown up in London.

At Wednesday afternoon study

hall, her student Deborah Adesodun

gave Price a piece of creative

writing she wrote during

the block. The piece talked about

a young Black woman named

Maleeka. Titled They Say, Deborah’s

writing later became the

basis of the song Gillespie performed

in Carnegie Hall three

years later.

Once the poem was done, Russell,

who has been dancing since

childhood, choreographed an

original dance to accompany it.

The pair took to Zankel Hall at

Carnegie Hall on Feb. 27 to perform

their collaborative work.

But, statistically speaking,

the arts among their peers is dying.

While Gillespie and Russell

live passionately through dance

and music, Price sees an increasing

“missed opportunity” for her

high school students.

New York falls into the 42

percent of US states that do not

define the arts as a core or academic

subject, according to The

National Center for Education

Statistics. On the flip side, 53

percent of tourist spending in

the state is spent on restaurants,

shopping, arts, culture, and entertainment,

the state comptroller’s

office reported last April.

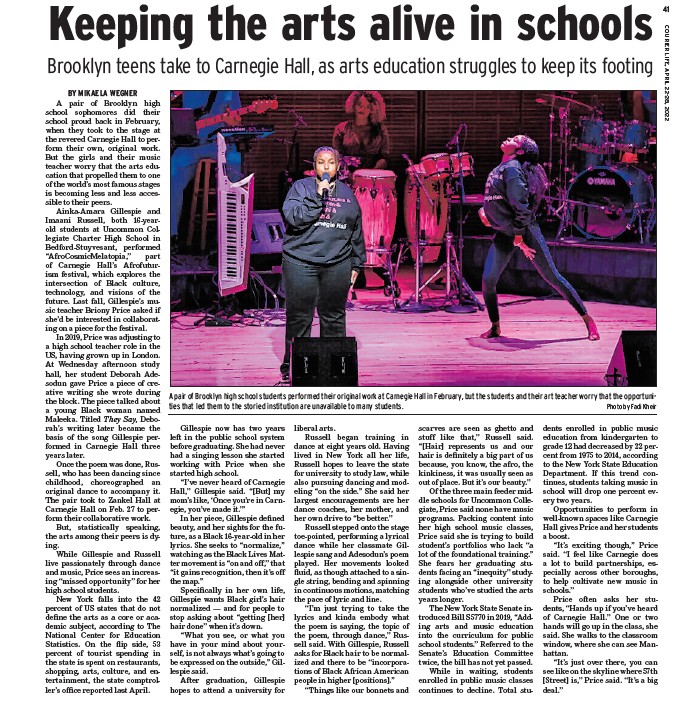

A pair of Brooklyn high school students performed their original work at Carnegie Hall in February, but the students and their art teacher worry that the opportunities

that led them to the storied institution are unavailable to many students. Photo by Fadi Kheir

Gillespie now has two years

left in the public school system

before graduating. She had never

had a singing lesson she started

working with Price when she

started high school.

“I’ve never heard of Carnegie

Hall,” Gillespie said. “But my

mom’s like, ‘Once you’re in Carnegie,

you’ve made it.’”

In her piece, Gillespie defined

beauty, and her sights for the future,

as a Black 16-year-old in her

lyrics. She seeks to “normalize,”

watching as the Black Lives Matter

movement is “on and off,” that

“it gains recognition, then it’s off

the map.”

Specifically in her own life,

Gillespie wants Black girl’s hair

normalized — and for people to

stop asking about “getting her

hair done” when it’s down.

“What you see, or what you

have in your mind about yourself,

is not always what’s going to

be expressed on the outside,” Gillespie

said.

After graduation, Gillespie

hopes to attend a university for

liberal arts.

Russell began training in

dance at eight years old. Having

lived in New York all her life,

Russell hopes to leave the state

for university to study law, while

also pursuing dancing and modeling

“on the side.” She said her

largest encouragements are her

dance coaches, her mother, and

her own drive to “be better.”

Russell stepped onto the stage

toe-pointed, performing a lyrical

dance while her classmate Gillespie

sang and Adesodun’s poem

played. Her movements looked

fluid, as though attached to a single

string, bending and spinning

in continuous motions, matching

the pace of lyric and line.

“I’m just trying to take the

lyrics and kinda embody what

the poem is saying, the topic of

the poem, through dance,” Russell

said. With Gillespie, Russell

asks for Black hair to be normalized

and there to be “incorporations

of Black African American

people in higher positions.”

“Things like our bonnets and

scarves are seen as ghetto and

stuff like that,” Russell said.

“Hair represents us and our

hair is definitely a big part of us

because, you know, the afro, the

kinkiness, it was usually seen as

out of place. But it’s our beauty.”

Of the three main feeder middle

schools for Uncommon Collegiate,

Price said none have music

programs. Packing content into

her high school music classes,

Price said she is trying to build

student’s portfolios who lack “a

lot of the foundational training.”

She fears her graduating students

facing an “inequity” studying

alongside other university

students who’ve studied the arts

years longer.

The New York State Senate introduced

Bill S5770 in 2019, “Adding

arts and music education

into the curriculum for public

school students.” Referred to the

Senate’s Education Committee

twice, the bill has not yet passed.

While in waiting, students

enrolled in public music classes

continues to decline. Total students

enrolled in public music

education from kindergarten to

grade 12 had decreased by 22 percent

from 1975 to 2014, according

to the New York State Education

Department. If this trend continues,

students taking music in

school will drop one percent every

two years.

Opportunities to perform in

well-known spaces like Carnegie

Hall gives Price and her students

a boost.

“It’s exciting though,” Price

said. “I feel like Carnegie does

a lot to build partnerships, especially

across other boroughs,

to help cultivate new music in

schools.”

Price often asks her students,

“Hands up if you’ve heard

of Carnegie Hall.” One or two

hands will go up in the class, she

said. She walks to the classroom

window, where she can see Manhattan.

“It’s just over there, you can

see like on the skyline where 57th

Street is,” Price said. “It’s a big

deal.”