Gas prices leave Brooklyn

drivers, businesses feeling

infl ation pain at the pump

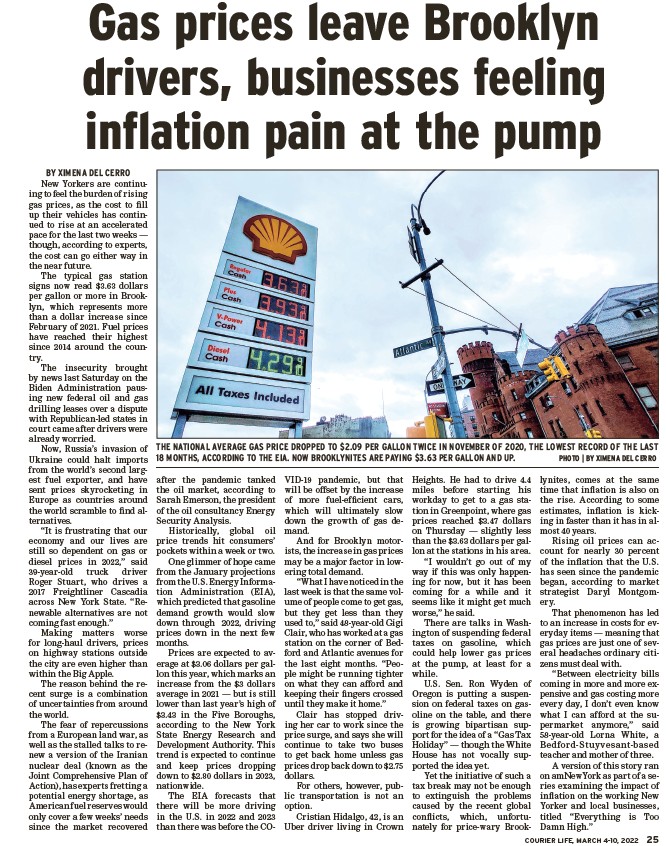

THE NATIONAL AVERAGE GAS PRICE DROPPED TO $2.09 PER GALLON TWICE IN NOVEMBER OF 2020, THE LOWEST RECORD OF THE LAST

18 MONTHS, ACCORDING TO THE EIA. NOW BROOKLYNITES ARE PAYING $3.63 PER GALLON AND UP. PHOTO | BY XIMENA DEL CERRO

COURIER LIFE, MARCH 4-10, 2022 25

BY XIMENA DEL CERRO

New Yorkers are continuing

to feel the burden of rising

gas prices, as the cost to fi ll

up their vehicles has continued

to rise at an accelerated

pace for the last two weeks —

though, according to experts,

the cost can go either way in

the near future.

The typical gas station

signs now read $3.63 dollars

per gallon or more in Brooklyn,

which represents more

than a dollar increase since

February of 2021. Fuel prices

have reached their highest

since 2014 around the country.

The insecurity brought

by news last Saturday on the

Biden Administration pausing

new federal oil and gas

drilling leases over a dispute

with Republican-led states in

court came after drivers were

already worried.

Now, Russia’s invasion of

Ukraine could halt imports

from the world’s second largest

fuel exporter, and have

sent prices skyrocketing in

Europe as countries around

the world scramble to fi nd alternatives.

“It is frustrating that our

economy and our lives are

still so dependent on gas or

diesel prices in 2022,” said

39-year-old truck driver

Roger Stuart, who drives a

2017 Freightliner Cascadia

across New York State. “Renewable

alternatives are not

coming fast enough.”

Making matters worse

for long-haul drivers, prices

on highway stations outside

the city are even higher than

within the Big Apple.

The reason behind the recent

surge is a combination

of uncertainties from around

the world.

The fear of repercussions

from a European land war, as

well as the stalled talks to renew

a version of the Iranian

nuclear deal (known as the

Joint Comprehensive Plan of

Action), has experts fretting a

potential energy shortage, as

American fuel reserves would

only cover a few weeks’ needs

since the market recovered

after the pandemic tanked

the oil market, according to

Sarah Emerson, the president

of the oil consultancy Energy

Security Analysis.

Historically, global oil

price trends hit consumers’

pockets within a week or two.

One glimmer of hope came

from the January projections

from the U.S. Energy Information

Administration (EIA),

which predicted that gasoline

demand growth would slow

down through 2022, driving

prices down in the next few

months.

Prices are expected to average

at $3.06 dollars per gallon

this year, which marks an

increase from the $3 dollars

average in 2021 — but is still

lower than last year’s high of

$3.43 in the Five Boroughs,

according to the New York

State Energy Research and

Development Authority. This

trend is expected to continue

and keep prices dropping

down to $2.80 dollars in 2023,

nationwide.

The EIA forecasts that

there will be more driving

in the U.S. in 2022 and 2023

than there was before the COVID

19 pandemic, but that

will be offset by the increase

of more fuel-effi cient cars,

which will ultimately slow

down the growth of gas demand.

And for Brooklyn motorists,

the increase in gas prices

may be a major factor in lowering

total demand.

“What I have noticed in the

last week is that the same volume

of people come to get gas,

but they get less than they

used to,” said 48-year-old Gigi

Clair, who has worked at a gas

station on the corner of Bedford

and Atlantic avenues for

the last eight months. “People

might be running tighter

on what they can afford and

keeping their fi ngers crossed

until they make it home.”

Clair has stopped driving

her car to work since the

price surge, and says she will

continue to take two buses

to get back home unless gas

prices drop back down to $2.75

dollars.

For others, however, public

transportation is not an

option.

Cristian Hidalgo, 42, is an

Uber driver living in Crown

Heights. He had to drive 4.4

miles before starting his

workday to get to a gas station

in Greenpoint, where gas

prices reached $3.47 dollars

on Thursday — slightly less

than the $3.63 dollars per gallon

at the stations in his area.

“I wouldn’t go out of my

way if this was only happening

for now, but it has been

coming for a while and it

seems like it might get much

worse,” he said.

There are talks in Washington

of suspending federal

taxes on gasoline, which

could help lower gas prices

at the pump, at least for a

while.

U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden of

Oregon is putting a suspension

on federal taxes on gasoline

on the table, and there

is growing bipartisan support

for the idea of a “Gas Tax

Holiday” — though the White

House has not vocally supported

the idea yet.

Yet the initiative of such a

tax break may not be enough

to extinguish the problems

caused by the recent global

confl icts, which, unfortunately

for price-wary Brooklynites,

comes at the same

time that infl ation is also on

the rise. According to some

estimates, infl ation is kicking

in faster than it has in almost

40 years.

Rising oil prices can account

for nearly 30 percent

of the infl ation that the U.S.

has seen since the pandemic

began, according to market

strategist Daryl Montgomery.

That phenomenon has led

to an increase in costs for everyday

items — meaning that

gas prices are just one of several

headaches ordinary citizens

must deal with.

“Between electricity bills

coming in more and more expensive

and gas costing more

every day, I don’t even know

what I can afford at the supermarket

anymore,” said

58-year-old Lorna White, a

Bedford-Stuyvesant-based

teacher and mother of three.

A version of this story ran

on amNewYork as part of a series

examining the impact of

infl ation on the working New

Yorker and local businesses,

titled “Everything is Too

Damn High.”