Back from the rubble

Landmarks panel oks plan to rebuild demolished facades

BY MAX PARROTT

When the city ordered

the demolition of nine

landmarked houses in

the Gansevoort Market Historic

District in the midst of a restorative

construction project

it effectively reduced the developer’s

plans to rubble. On Jan.

8, the city’s Landmarks Preservation

Commission greenlit

a new plan to fi nish the project

using the original bricks from

the raised historical buildings.

The plans to build on the

plot of landmarked brick 1840s

rowhouses, located at 44-54

Ninth Ave. and 351-55 West

14th St. in the Meatpacking

District, has long been a magnet

of controversy among the

neighborhood’s preservationists.

But the sudden demolition

of the historic brick exteriors

sparked outrage.

In the summer of 2020, the

LPC approved the developer’s

plan to construct a nine-story

commercial tower behind the

landmarked facades of the rowhouse

with the condition that

it expand the scope of its effort

to preserve the landmarked

exteriors of the original buildings

and reduce the size of

LOCAL NEWS

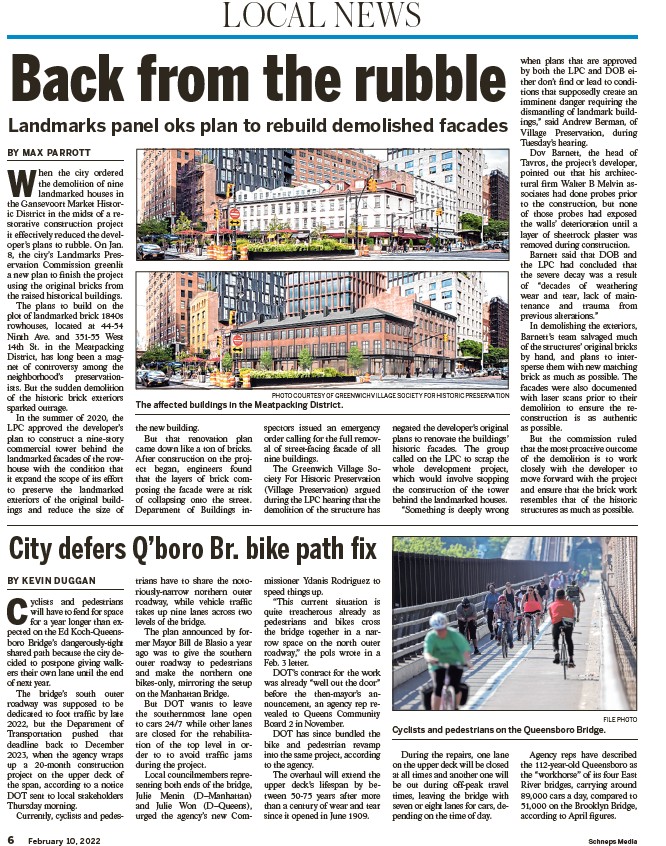

The aff ected buildings in the Meatpacking District.

the new building.

But that renovation plan

came down like a ton of bricks.

After construction on the project

began, engineers found

that the layers of brick composing

the facade were at risk

of collapsing onto the street.

Department of Buildings inspectors

PHOTO COURTESY OF GREENWICH VILLAGE SOCIETY FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION

issued an emergency

order calling for the full removal

of street-facing facade of all

nine buildings.

The Greenwich Village Society

For Historic Preservation

(Village Preservation) argued

during the LPC hearing that the

demolition of the structure has

negated the developer’s original

plans to renovate the buildings’

historic facades. The group

called on the LPC to scrap the

whole development project,

which would involve stopping

the construction of the tower

behind the landmarked houses.

“Something is deeply wrong

when plans that are approved

by both the LPC and DOB either

don’t fi nd or lead to conditions

that supposedly create an

imminent danger requiring the

dismantling of landmark buildings,”

said Andrew Berman, of

Village Preservation, during

Tuesday’s hearing.

Dov Barnett, the head of

Tavros, the project’s developer,

pointed out that his architectural

fi rm Walter B Melvin associates

had done probes prior

to the construction, but none

of those probes had exposed

the walls’ deterioration until a

layer of sheetrock plaster was

removed during construction.

Barnett said that DOB and

the LPC had concluded that

the severe decay was a result

of “decades of weathering

wear and tear, lack of maintenance

and trauma from

previous alterations.”

In demolishing the exteriors,

Barnett’s team salvaged much

of the structures’ original bricks

by hand, and plans to intersperse

them with new matching

brick as much as possible. The

facades were also documented

with laser scans prior to their

demolition to ensure the reconstruction

is as authentic

as possible.

But the commission ruled

that the most proactive outcome

of the demolition is to work

closely with the developer to

move forward with the project

and ensure that the brick work

resembles that of the historic

structures as much as possible.

City defers Q’boro Br. bike path fi x

BY KEVIN DUGGAN

Cyclists and pedestrians

will have to fend for space

for a year longer than expected

on the Ed Koch-Queensboro

Bridge’s dangerously-tight

shared path because the city decided

to postpone giving walkers

their own lane until the end

of next year.

The bridge’s south outer

roadway was supposed to be

dedicated to foot traffi c by late

2022, but the Department of

Transportation pushed that

deadline back to December

2023, when the agency wraps

up a 20-month construction

project on the upper deck of

the span, according to a notice

DOT sent to local stakeholders

Thursday morning.

Currently, cyclists and pedestrians

have to share the notoriously

narrow northern outer

roadway, while vehicle traffi c

takes up nine lanes across two

levels of the bridge.

The plan announced by former

Mayor Bill de Blasio a year

ago was to give the southern

outer roadway to pedestrians

and make the northern one

bikes-only, mirroring the setup

on the Manhattan Bridge.

But DOT wants to leave

the southernmost lane open

to cars 24/7 while other lanes

are closed for the rehabilitation

of the top level in order

to to avoid traffi c jams

during the project.

Local councilmembers representing

both ends of the bridge,

Julie Menin (D–Manhattan)

and Julie Won (D–Queens),

urged the agency’s new Commissioner

Ydanis Rodriguez to

speed things up.

“This current situation is

quite treacherous already as

pedestrians and bikes cross

the bridge together in a narrow

space on the north outer

roadway,” the pols wrote in a

Feb. 3 letter.

DOT’s contract for the work

was already “well out the door”

before the then-mayor’s announcement,

an agency rep revealed

to Queens Community

Board 2 in November.

DOT has since bundled the

bike and pedestrian revamp

into the same project, according

to the agency.

The overhaul will extend the

upper deck’s lifespan by between

50-75 years after more

than a century of wear and tear

since it opened in June 1909.

Cyclists and pedestrians on the Queensboro Bridge.

During the repairs, one lane

on the upper deck will be closed

at all times and another one will

be out during off-peak travel

times, leaving the bridge with

seven or eight lanes for cars, depending

on the time of day.

FILE PHOTO

Agency reps have described

the 112-year-old Queensboro as

the “workhorse” of its four East

River bridges, carrying around

89,000 cars a day, compared to

51,000 on the Brooklyn Bridge,

according to April fi gures.

6 February 10, 2022 Schneps Media