29

Caribbean Life, April 14-20, 2022

Based on a real-life court case, this book tells the tale slowly

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Some things, well, you just

make them your own.

You know it happens when you

just can’t let something go. You

turn it over in your mind six ways

daily, and talk about it until everybody

around you’s sick of hearing

about it. Pretty soon, it’s your

problem to have but be careful: as

in the new novel, “Take My Hand”

by Dolen Perkins-Valdez, these

kinds of things change lives.

If you’d have asked her, Civil

Townsend couldn’t exactly tell you

why she was on a road trip, alone,

heading from Memphis to Birmingham.

Maybe it was because

she’d heard that India was sick

with cancer. Maybe it was guilt.

She wondered if India would

even remember her. It had been

more than forty years since Civil

last saw her. India was a girl

then.

In a way, so was Civil.

That was 1973, a year of women’s

rights and political upheaval,

and she was fresh out of school, a

new nurse at her first job at a family

planning clinic in Birmingham.

The clinic was funded by the government

and most of its clientele

were poor, a fact that was hard:

Civil had grown up with privileges

that few Black Alabamans

enjoyed, and she’d been made to

fear the people who looked like

her, but were not like her at all.

Wasn’t it ironic, then, that the

first folder she received on her

first day at work was for Erica and

India Williams, two girls who were

living in squalor, filthy, and illiterate?

Wasn’t it ironic that Civil was

told to give those little girls birth

control shots that could make

them sick when she, herself, was

carrying a birth-related secret?

Reluctance to do her job led to

rebellion, which led her to try to

make a difference in the lives of

the girls, their father, and their

grandmother. Civil stepped in and

got them new housing, new clothing,

and new lives. But she didn’t

help in the end, she made things

worse.

Would her own daughter would

understand someday?

Based loosely on a real-life, historic

case, “Take My Hand” seems

poised for an outrage that only

barely arrives, perhaps because

the reason for the railing is overshadowed

by the main character,

fussing at herself and her own

decisions. In the beginning, in

fact, author Dolen Perkins-Valdez

doesn’t make her Civil very likable;

even Civil admits that she’s

“uppity” and that never really

goes away.

As for the plot, well, it’s slow

– except when it’s not, and then

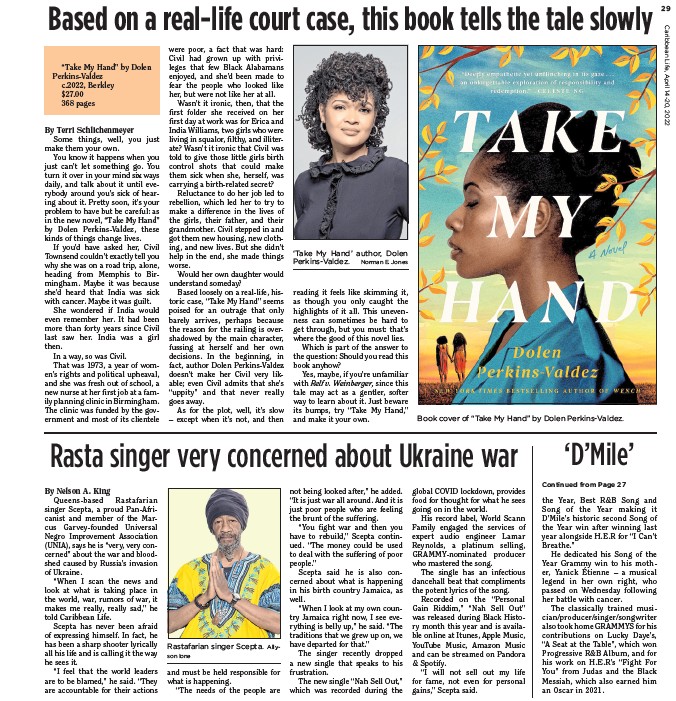

‘Take My Hand’ author, Dolen

Perkins-Valdez. Norman E. Jones

reading it feels like skimming it,

as though you only caught the

highlights of it all. This unevenness

can sometimes be hard to

get through, but you must: that’s

where the good of this novel lies.

Which is part of the answer to

the question: Should you read this

book anyhow?

Yes, maybe, if you’re unfamiliar

with Relf v. Weinberger, since this

tale may act as a gentler, softer

way to learn about it. Just beware

its bumps, try “Take My Hand,”

and make it your own.

“Take My Hand” by Dolen

Perkins-Valdez

c.2022, Berkley

$27.00

368 pages

Book cover of “Take My Hand” by Dolen Perkins-Valdez.

Rasta singer very concerned about Ukraine war

By Nelson A. King

Queens-based Rastafarian

singer Scepta, a proud Pan-Africanist

and member of the Marcus

Garvey-founded Universal

Negro Improvement Association

(UNIA), says he is “very, very concerned”

about the war and bloodshed

caused by Russia’s invasion

of Ukraine.

“When I scan the news and

look at what is taking place in

the world, war, rumors of war, it

makes me really, really sad,” he

told Caribbean Life.

Scepta has never been afraid

of expressing himself. In fact, he

has been a sharp shooter lyrically

all his life and is calling it the way

he sees it.

“I feel that the world leaders

are to be blamed,” he said. “They

are accountable for their actions

and must be held responsible for

what is happening.

“The needs of the people are

not being looked after,” he added.

“It is just war all around. And it is

just poor people who are feeling

the brunt of the suffering.

“You fight war and then you

have to rebuild,” Scepta continued.

“The money could be used

to deal with the suffering of poor

people.”

Scepta said he is also concerned

about what is happening

in his birth country Jamaica, as

well.

“When I look at my own country

Jamaica right now, I see everything

is belly up,” he said. “The

traditions that we grew up on, we

have departed for that.”

The singer recently dropped

a new single that speaks to his

frustration.

The new single “Nah Sell Out,”

which was recorded during the

global COVID lockdown, provides

food for thought for what he sees

going on in the world.

His record label, World Scann

Family engaged the services of

expert audio engineer Lamar

Reynolds, a platinum selling,

GRAMMY-nominated producer

who mastered the song.

The single has an infectious

dancehall beat that compliments

the potent lyrics of the song.

Recorded on the “Personal

Gain Riddim,” “Nah Sell Out”

was released during Black History

month this year and is available

online at Itunes, Apple Music,

YouTube Music, Amazon Music

and can be streamed on Pandora

& Spotify.

“I will not sell out my life

for fame, not even for personal

gains,” Scepta said.

‘D’Mile’

Continued from Page 27

the Year, Best R&B Song and

Song of the Year making it

D’Mile’s historic second Song of

the Year win after winning last

year alongside H.E.R for “I Can’t

Breathe.”

He dedicated his Song of the

Year Grammy win to his mother,

Yanick Étienne – a musical

legend in her own right, who

passed on Wednesday following

her battle with cancer.

The classically trained musician/

producer/singer/songwriter

also took home GRAMMYS for his

contributions on Lucky Daye’s,

“A Seat at the Table”, which won

Progressive R&B Album, and for

his work on H.E.R’s “Fight For

You” from Judas and the Black

Messiah, which also earned him

an Oscar in 2021.

Rastafarian singer Scepta. Allyson

Ione