Did You Know About….?

Caribbean Life, OCT. 29-NOV. 4, 2021 43

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Tis the season of giving.

A few coins in a bucket, folded

dollars in an envelope, an

extra donation to the church,

you don’t mind. Wrap a small

gift for a child in need, give to

someone who has nothing, it’s

the holidays. Or read “Until I

Am Free” by Keisha N. Blain,

and give of yourself.

From the day she was born

in Mississippi in the fall of

1917, Fannie Lou Townsend

knew only poverty. She was the

youngest of 20 children, and

her parents were mostly sharecroppers;

because they needed

every pair of hands to keep

ahead, Fannie Lou often stayed

home from school to help,

beginning right at age six.

As a younger woman, Fannie

Lou stayed on the same

plantation where she was born

and though she seemed to live

a quiet life, there were hints of

mid-twentieth-century scandal:

documents show that she

may’ve been wedded to a man

named Gray before marrying

Percy “Pap” Hamer in 1944.

She never birthed any children;

it’s said that she tried to, but

was sterilized without her permission

in 1961, a fact that she

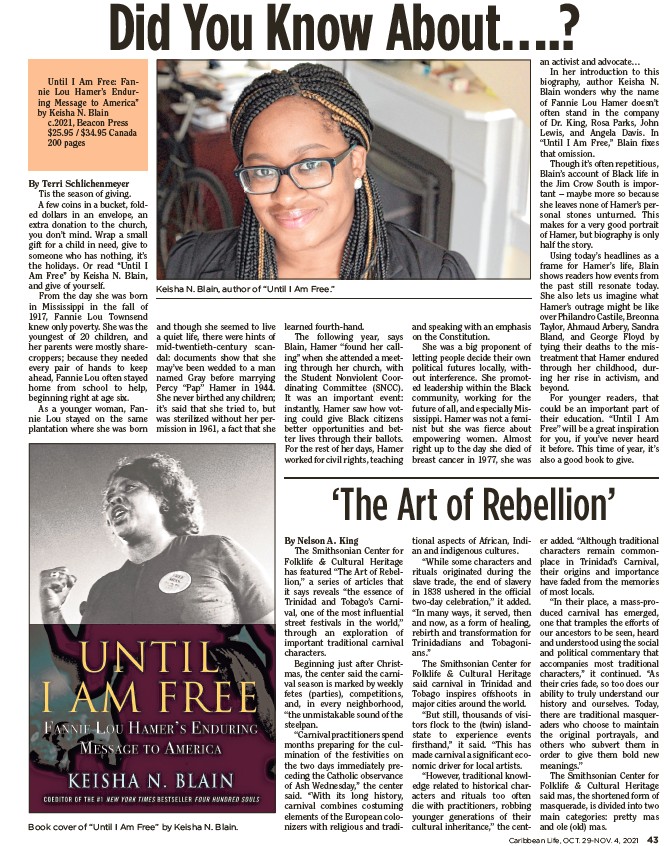

Book cover of “Until I Am Free” by Keisha N. Blain.

learned fourth-hand.

The following year, says

Blain, Hamer “found her calling”

when she attended a meeting

through her church, with

the Student Nonviolent Coordinating

Committee (SNCC).

It was an important event:

instantly, Hamer saw how voting

could give Black citizens

better opportunities and better

lives through their ballots.

For the rest of her days, Hamer

worked for civil rights, teaching

and speaking with an emphasis

on the Constitution.

She was a big proponent of

letting people decide their own

political futures locally, without

interference. She promoted

leadership within the Black

community, working for the

future of all, and especially Mississippi.

Hamer was not a feminist

but she was fierce about

empowering women. Almost

right up to the day she died of

breast cancer in 1977, she was

an activist and advocate…

In her introduction to this

biography, author Keisha N.

Blain wonders why the name

of Fannie Lou Hamer doesn’t

often stand in the company

of Dr. King, Rosa Parks, John

Lewis, and Angela Davis. In

“Until I Am Free,” Blain fixes

that omission.

Though it’s often repetitious,

Blain’s account of Black life in

the Jim Crow South is important

– maybe more so because

she leaves none of Hamer’s personal

stones unturned. This

makes for a very good portrait

of Hamer, but biography is only

half the story.

Using today’s headlines as a

frame for Hamer’s life, Blain

shows readers how events from

the past still resonate today.

She also lets us imagine what

Hamer’s outrage might be like

over Philandro Castile, Breonna

Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Sandra

Bland, and George Floyd by

tying their deaths to the mistreatment

that Hamer endured

through her childhood, during

her rise in activism, and

beyond.

For younger readers, that

could be an important part of

their education. “Until I Am

Free” will be a great inspiration

for you, if you’ve never heard

it before. This time of year, it’s

also a good book to give.

Until I Am Free: Fannie

Lou Hamer’s Enduring

Message to America”

by Keisha N. Blain

c.2021, Beacon Press

$25.95 / $34.95 Canada

200 pages

Keisha N. Blain, author of “Until I Am Free.”

‘The Art of Rebellion’

By Nelson A. King

The Smithsonian Center for

Folklife & Cultural Heritage

has featured “The Art of Rebellion,”

a series of articles that

it says reveals “the essence of

Trinidad and Tobago’s Carnival,

one of the most influential

street festivals in the world,”

through an exploration of

important traditional carnival

characters.

Beginning just after Christmas,

the center said the carnival

season is marked by weekly

fetes (parties), competitions,

and, in every neighborhood,

“the unmistakable sound of the

steelpan.

“Carnival practitioners spend

months preparing for the culmination

of the festivities on

the two days immediately preceding

the Catholic observance

of Ash Wednesday,” the center

said. “With its long history,

carnival combines costuming

elements of the European colonizers

with religious and traditional

aspects of African, Indian

and indigenous cultures.

“While some characters and

rituals originated during the

slave trade, the end of slavery

in 1838 ushered in the official

two-day celebration,” it added.

“In many ways, it served, then

and now, as a form of healing,

rebirth and transformation for

Trinidadians and Tobagonians.”

The Smithsonian Center for

Folklife & Cultural Heritage

said carnival in Trinidad and

Tobago inspires offshoots in

major cities around the world.

“But still, thousands of visitors

flock to the (twin) islandstate

to experience events

firsthand,” it said. “This has

made carnival a significant economic

driver for local artists.

“However, traditional knowledge

related to historical characters

and rituals too often

die with practitioners, robbing

younger generations of their

cultural inheritance,” the center

added. “Although traditional

characters remain commonplace

in Trinidad’s Carnival,

their origins and importance

have faded from the memories

of most locals.

“In their place, a mass-produced

carnival has emerged,

one that tramples the efforts of

our ancestors to be seen, heard

and understood using the social

and political commentary that

accompanies most traditional

characters,” it continued. “As

their cries fade, so too does our

ability to truly understand our

history and ourselves. Today,

there are traditional masqueraders

who choose to maintain

the original portrayals, and

others who subvert them in

order to give them bold new

meanings.”

The Smithsonian Center for

Folklife & Cultural Heritage

said mas, the shortened form of

masquerade, is divided into two

main categories: pretty mas

and ole (old) mas.