Members of 2001 Mets refl ect on their role

BY JOE PANTORNO

The tears along the tapestry

that is the history of the United

States are stark and unpleasant

— ranging from a Civil War to

natural disasters, pandemics

and attacks on home soil, to

name just a few. Through the

years, baseball has become so

ingrained in American culture

that it has been looked upon

to heal the nation during hard

times.

This Sept. 11 marks the 20th

anniversary of the worst terrorist

attack conducted upon

American shores as nearly

3,000 people were killed in a

calculated assault carried out

by al-Qaeda. Two planes struck

the twin towers of the World

Trade Center in New York City;

a third plane hit the Pentagon

just outside Washington, D.C.;

and a fourth plane was heroically

forced down in Shanksville,

PA.

As a nation came to terms

with the shock of the unthinkable

happening in their proverbial

backyards, mourning

the loss of thousands, and the

seemingly insurmountable

task of trying to recover, baseball

once again was not too far

behind to help — ever so slightly

— alleviate the pain that is

still felt so deeply by so many

two decades later.

And the New York Mets led

the way.

Confusion

Following a mostly difficult

August, the defending National

League champion Mets were

surging at the right time in

hopes of nabbing a spot in the

2001 playoffs. After taking two

of three from the then-Florida

Marlins, the Mets had won 10 of

their last 12 and traveled from

Miami to Pittsburgh on Sept. 10

for a three-game set against the

Pirates.

“We get to Pittsburgh

around 3 in the morning

and when you travel, you go

straight from the airport to

the hotel and check-in, go to

your room and go to sleep,”

said Edgardo Alfonzo, Mets

Hall of Famer and the team’s

second baseman in 2001. “My

wife knew that every time we

traveled, we get in early in the

morning. So it surprised me

when she called at like, 9 in the

morning.”

“‘Put the news on. Something

happened,’” Alfonzo recounted

his wife telling him.

The first plane had just

struck the North Tower of the

World Trade Center.

“I turned on the TV and

I caught the news between

the first and second airplane

strikes,” said former first baseman

Todd Zeile, who was two

days removed from his 36th

birthday at the time. “At first,

it seemed like a really bizarre,

random story of a plane out of

TIMESLEDGER | QNS.4 COM | SEPT. 10 - SEPT. 16, 2021

its flight path ending up in the

tower, and then watching live

as the second one struck, it

became a totally different feeling.”

So sunk in the reality that

the United States was under attack.

“It was a feeling of confusion,

a feeling of dread. I don’t

think anyone really anticipated

at that time what was going

on. It was ‘wait, how is this

possible?’” Zeile said. “There’s

confusion when you’ve grown

up without that kind of activity

on your own shore and I

think that was, to me, what

resonated. We’ve heard about

terrorist activity all over the

world but it never has been at

home.

“And it was literally at

home. I was living in New York

and a part of this Mets team

and I felt a part of this city.”

So did most of the Mets,

most particularly pitchers

John Franco, from Brooklyn,

and Al Leiter, from Toms River,

NJ.

“Johnny tried calling home.

The line was out. The service

was off completely,” Alfonzo

said. “It was scary.”

While glued to their television

sets at the Westin Hotel,

which was connected to the

William S. Moorhead Federal

Building, it was discovered

that Flight 93 — which took off

from Newark, NJ — veered off

course and was heading toward

the Pittsburgh area, prompting

the Mets to evacuate from the

hotel.

“We went to a hotel up in

the mountains and we were

wondering, ‘What are we going

to do here?’” Alfonzo said. “So

we were waiting to see what the

next move was for us.”

Over the next hour, the towers

collapsed, Flight 77 crashed

into the Pentagon and Flight

93 went down in that field in

Shanksville.

Finding their way home

With the airports shut

down, the Mets were able to get

a pair of busses on the night

of Sept. 11 to take them back

to New York — a trip that will

forever stick in the minds of

every player and staff member

on board.

“I remember being quiet

and generally MLB bus rides

aren’t quiet,” starting pitcher

Glendon Rusch, who was 26 at

the time, said. “Many of the

times we travel, everyone has

a pretty good time, but this one

was quiet. Very somber and

everyone was in disbelief … I

don’t think anyone knew how

to handle that situation with us

being in our 20s and 30s.”

“There had been talking

on the way home that was different

than anything ever discussed

on a major-league or

minor-league bus ride,” Zeile

added. “I think the camaraderie

that was building, and then

we got to the bridge.”

The George Washington

Bridge provides one of the most

breathtaking views of lower

Manhattan but as the sevenhour

trip entered the heart

of New York City at roughly

2 a.m., only more weight was

added to the gravity of the situation.

“I remember seeing fire

and smoke and wreckage from

a distance,” Rusch said. “That

area was kind of aglow with

fire and orange … Very sad to

see what was going on and it

only got worse once we really

took in the magnitude of what

was happening.”

Getting to work

Shea Stadium, the former

home of the Mets, was just 16

miles away from Ground Zero

and was viewed as a vital landmark

with the space and capac-

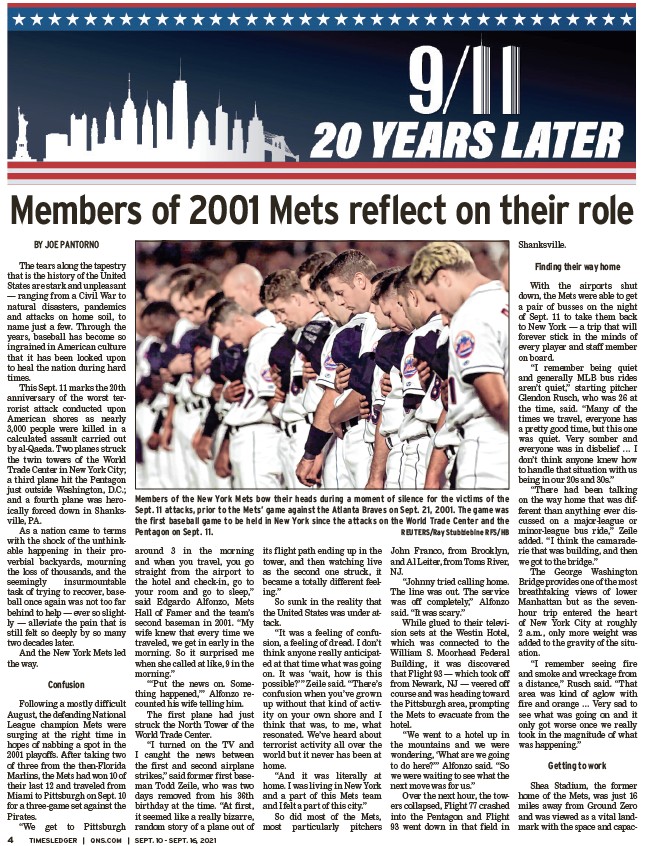

Members of the New York Mets bow their heads during a moment of silence for the victims of the

Sept. 11 attacks, prior to the Mets’ game against the Atlanta Braves on Sept. 21, 2001. The game was

the first baseball game to be held in New York since the attacks on the World Trade Center and the

Pentagon on Sept. 11. REUTERS/Ray Stubblebine RFS/HB